The impact of climate change

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. Five talented reporters are participating in a week-long state-of-the-art training program.

In this project we are highlighting the experiences of people whose lives are being affected by climate change.

Frank Bibeau is an Ojibwe attorney who grew up canoeing in the lakes and rivers of Northern Minnesota, fishing and harvesting wild rice with his family. He is now using Rights of Nature — an innovative legal movement that protects water, animals and ecosystems by giving them legal rights —to see if wild rice can stop a pipeline.

Illustration by EeJoon Choi

Leveraging treaty rights and wild rice, Ojibwe attorney takes on pipeline

Growing up, Frank Bibeau moved around a lot. But wherever the family was, his grandfather made sure they always had at least a few pounds of wild rice. And every summer, Bibeau would return to the White Earth Ojibwe reservation in Minnesota to harvest wild rice in his grandfather’s canoe.

“It is really a romantic kind of a concept, you know, to go out on a nice autumn day and be out there in the sun and all the animals are out there,” he said. “And you’re picking rice the way people have picked for thousands of years.”

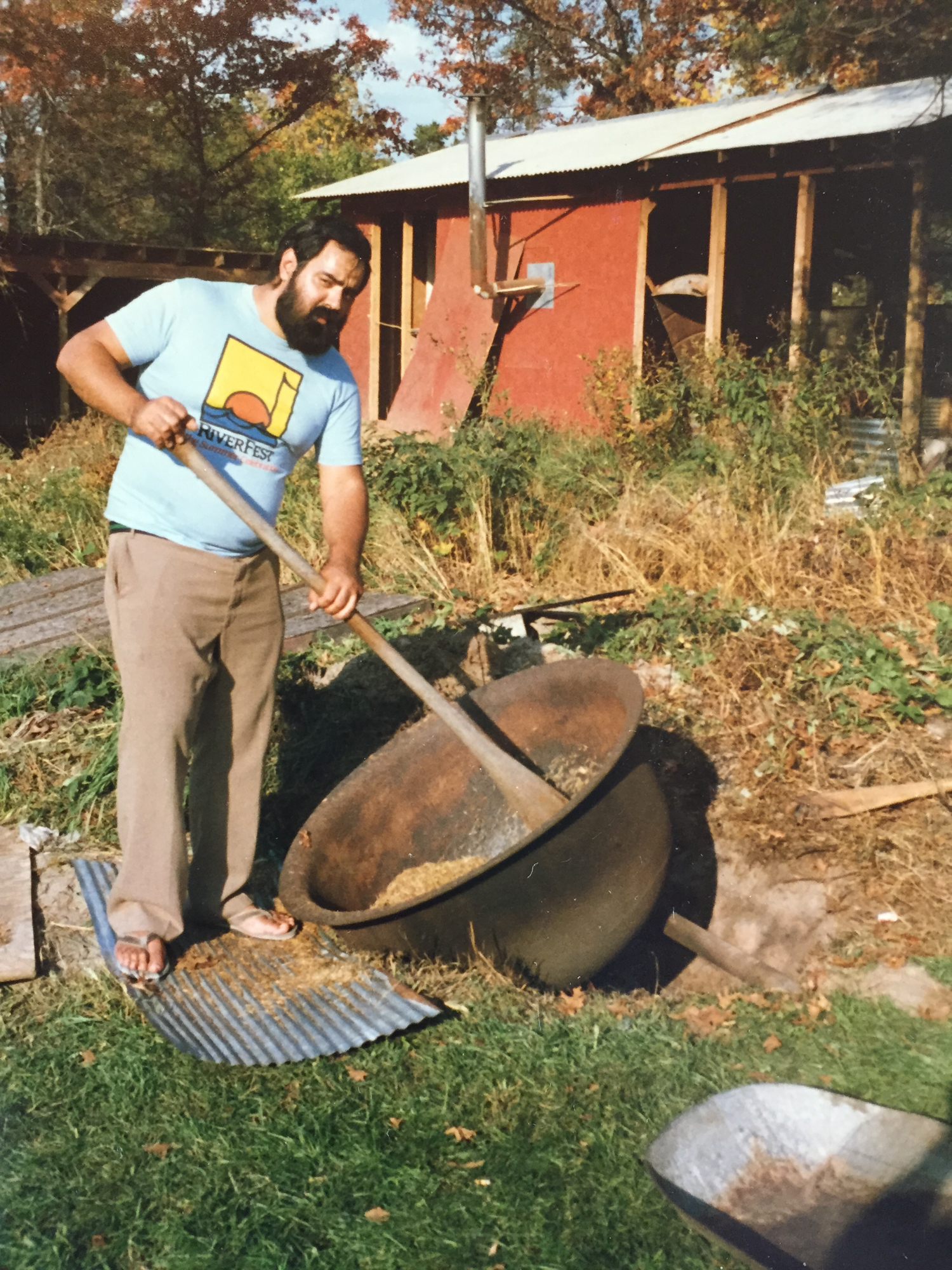

After he moved to the reservation in 1982, Bibeau inherited the canoe and his cousin’s wild rice plant. He now helps community members to harvest wild rice and learn about the cultural significance it holds for the Ojibwe.

“It’s still very significant,” Bibeau said. “You know, it’s still a huge part of all of our spirit dishes. It’s part of all of our ceremonies or celebrations.”

Bibeau is now using Rights of Nature — an innovative legal movement that protects water, animals and ecosystems by giving them legal rights — to see if wild rice can stop a pipeline.

LISTEN TO THE STORY

Wild rice, which the Ojibwe call Manoomin (meaning “good berry”), is an important part of Ojibwe culture, diet and tradition. It is also an indicator species that signals whether or not the ecosystem is healthy. (Photo courtesy of Frank Bibeau)

Wild rice, and the waters it depends on, are now in danger from climate change and oil pipelines. Enbridge, a Canadian energy company, wants to expand Line 3, a controversial pipeline that Indigenous people and other environmental activists have fiercely opposed. Bibeau says the new corridor would run directly through wild rice beds and could threaten the environmental health of the whole area.

“You start to understand just how important wild rice has been to the people over centuries and how important it is for the future as well, not just as a resource and a food, but it’s also an indicator species, a keystone species in the environment,” said Bibeau. “And so when wild rice isn’t doing very well, then you know there’s other problems in the water or or in the air or other things.“

Frank Bibeau inherited his grandfather’s canoe and his cousin’s wild rice plant, which he now uses to process wild rice with traditional techniques. (Photo courtesy of Frank Bibeau)

In March, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources released a report showing that damage to groundwater from Line 3 Pipeline construction is much worse than previously thought. For Bibeau, the news was upsetting, but unsurprising.

“It’s always the same thing,” Bibeau said. “They get what they want and we get to clean up.”

So Bibeau, now an attorney for the White Earth Nation, is fighting back. Bibeau believes that Rights of Nature could be a gamechanger for tribes.

“We may have the key to protecting our environment that nobody else has thought of using,” he said.

In 2018, Bibeau helped the tribe write a law that recognized the rights of wild rice, which they call Manoomin (meaning “good berry”), to “exist, flourish, regenerate, and evolve.” The law relies on a section of an 1837 treaty between the Ojibwe and the U.S. government.

“I couldn’t figure out how to get authority over them to compel them to do anything we might want to do. And right in my brain, you know, it just clicked,” Bibeau said. “Wild rice is mentioned specifically in the 1837 Treaty. It talks about how we retain the rights to hunt fish and gather wild rice on the lakes and rivers and lands that we’re ceding. Well, that’s huge.”

In 2021, Bibeau used the Rights of Manoomin law to sue the State of Minnesota over the construction of the pipeline. The case is pending in both tribal and federal appeals courts.

Since Bibeau first developed Rights of Manoomin, other tribes have used it as a model. In 2019, the Yurok Tribe in Northern California adopted a resolution recognizing the rights of the Klamath River. In Seattle, the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe is suing the city over its hydroelectric dams on behalf of salmon. Bibeau believes that these two cases will be the next step in the growing Indigenous Rights of Nature movement and have the potential to lead to widespread use by tribes across the country.

“You become part of the symbiotic relationship where you have no choice but to stand up and be part of the protection of the destruction that’s been going on here with our environment, with climate change,” said Bibeau.

The Ojibwe have used canoes to harvest wild rice for thousands of years. Today, oil pipeline construction threatens to destroy the environment and water that wild rice and the region depend on. (Photo courtesy of Frank Bibeau)

In a setback for the case in March, the White Earth Ojibwe Appellate Court dismissed the tribe’s own lawsuit. The ruling said that the court does not have jurisdiction over non-tribal member activities on off-reservation land. The case is still awaiting a decision from a Federal appeals court over that exact question.

Thomas Linzey, senior legal counsel for the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights and a Rights of Nature expert, called the decision a “hiccup” that would not slow down the broader Rights of Nature movement. When he developed Rights of Manoomin, Bibeau worked with Linzey, who helped write the first American Rights of Nature resolution in 2006. Now, Linzey sees Rights of Nature laws popping up all over the country and he believes the momentum behind them will only continue to grow.

Bibeau also remains undeterred. He sees the legal setback as an opportunity to learn and continue exploring the potential of Rights of Nature. The work he is doing, he hopes, can serve as a model for other tribes and communities to use Rights of Nature to protect their land, water, and wildlife.

“We’re doing things that haven’t been done before,” he said. “There’s a lot more to be discovered about the power of treaty rights. It’s exciting.”

Wild rice harvesting is a community affair and Bibeau loves to get more people involved in the process to help them learn about Ojibwe culture. (Photo courtesy of Frank Bibeau)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The Next Generation Radio Project is a week-long digital journalism training project designed to give competitively selected participants, who are interested in radio and journalism, the skills and opportunity to report and produce their own multimedia story. Those chosen for the project are paired with a professional journalist who serves as their mentor.

This edition of the #NPRNextGenRadio project was produced in collaboration with:

- Managing Editors – Michelle Faust Raghavan - Independent Editor, Portland, Oregon; Phyllis Fletcher - Independent Editor, Seattle

- Digital Editors – Alexis L. Richardson, Chief Innovation Officer/Digital Content Strategist, Philadelphia; Lita Beck (Navajo) - Senior Politics Editor, The Philadelphia Inquirer; Heather C. Gomez (Jicarilla Apache) - Freelance Digital Editor, Dulce, New Mexico

- Audio Tech – Selena Seay-Reynolds - Freelance Audio Engineer, Los Angeles; Abby Fritz, Freelance Audio Tech/Producer, Syracuse, New York

- Editorial Illustrators – Lauren Ibañez, Freelance Editorial Illustrator, Houston; Eejoon Choi - Freelance Editorial Illustrator, Los Angeles; Ard Su - Freelance Editorial Illustrator, New York

- Visuals – Todd Michalek, Freelance Visual Journalist, Syracuse, New York

- Web Developer – Robert Boos, Freelance Creative Technologist, Minneapolis

Our journalist/mentors for this project were:

- Pauly Denetclaw - Politics Reporter, Indian Country Today, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Savannah Maher - Reporter, Marketplace, Albuquerque, New Mexico

- Taylar Stegner (Shoshone and Arapaho) - Tribal & Rural Reporter, Wyoming Public Radio

- Tarryn Mento - Reporting Fellow, WAER, Syracuse, New York

- Carrie Jung - Education Reporter, WBUR, Boston

NPR’s Next Generation Radio program is directed by its founder, Doug Mitchell.